Golden Dawn gained the third highest vote share in the European Parliament elections in Greece, translating into three MEPs. Sofia Vasilopoulou and Daphne Halikiopoulou assess the factors underpinning this success. They write that Golden Dawn’s ability to blend nationalism and populism into a coherent narrative is at the heart of their appeal, with the party now capable of attracting votes from across all sections of Greek society.

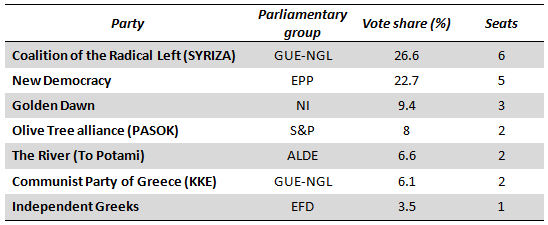

Radical right-wing parties have emerged as the main winners of the 2014 European Parliament elections. UKIP beat both its Labour and Conservative rivals with 27.5 per cent of the vote, translating into 24 MEPs. In France, the Front National topped the polls with 25 per cent and 24 MEPs. Radical right-wing parties came second in Hungary and third in Austria and Greece, where the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn emerged as the third party with just over 9 per cent, as shown in the Table below.

Table: Result of the 2014 European Parliament election in Greece

Note: Results are still provisional. PASOK is contesting the elections as part of the ‘Olive Tree’ alliance, which also includesAgreement for the New Greece, Dynamic Greece and the New Reformers. For information on the other parties see:Coalition of the; Radical Left (SYRIZA); New Democracy; Golden Dawn; The River (To Potami); Communist Party of Greece(KKE); Independent Greeks.

The Greek case is particularly interesting. Unlike in most cases where radical right-wing parties have sought to disassociate themselves from blatant extremism, not only is Golden Dawn openly violent and racist, but more importantly many of its MPs, including its leader, are currently in prison awaiting trial for charges including running a criminal organisation, murder and grievous bodily harm. How can a party whose members are facing criminal records to this extent have been so attractive to large numbers of Greek voters?

Assessing Golden Dawn’s success

This debate has been on-going in Greece since the murder of left-wing activist Pavlos Fyssas and the charges pressed against Golden Dawn MPs. Many have had their parliamentary immunity lifted. Yet recently the Greek Supreme Court ruled that, pending indictment, Golden Dawn remains legal and may run for elections.

On the one hand, EP elections are generally regarded as ‘second order’ elections. This means that there is a higher likelihood of protest votes since people may send a message of disillusionment and dissatisfaction to their government without necessarily giving a mandate for anti-establishment parties in the national parliament. On the other hand, the implication of this result for national politics is of paramount importance.

First, the rise of anti-establishment parties in Greece signals a vote of no confidence and may speed up the process of bringing about a national election. Second, the percentage received by Golden Dawn is consistent with the May and June 2012 national election results, as well as recent polls indicating that the party has managed to form a strong support base, ranging between 7 and 10 per cent. This can also be seen in the results for the recent local elections in Greece where although SYRIZA (the radical left-wing party that topped the EU election poll) did not perform as well as it did in the EU election, Golden Dawn support was consistent.

The answer lies in the ability of Golden Dawn to blend nationalism with populism. By presenting Europe as a problem of national exploitation, it has managed to turn the question of indictment on its head. The key issue the party draws on is national sovereignty. Greek nationalism provides fertile ground for Golden Dawn to draw on.

The party draws parallels with Greece’s historical battles for the restoration of national sovereignty, for instance against the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century and Nazi Germany in the 1940s. The rhetoric is one that emphasises the distinction between superior and inferior nations, the strong sense of Greek ethnic superiority and the portrayal of the Greek nation under threat, which far from being an alien discourse, forms the dominant narrative of Greek nationalism constantly maintained and reproduced through official institutions including the education system.

Appealing to those who consider themselves patriots, and have been let down by the political mainstream, Golden Dawn present a story in which the Greek predicament is a result of those foreign exploitative powers who seek to destroy Greece, and their domestic collaborators. The attempt to indict the party members is merely another example of this, an attempt by the ‘old rotten system’ to preserve the status quo by eradicating those who seek to restore true patriotic democracy.

The resonance of this story is what has gained Golden Dawn a stable electoral base. Many of its supporters may not believe that it is a neo-Nazi or neo-fascist party. This is why, perhaps unlike the other radical right-wing parties in Europe, Golden Dawn has managed to attract voters from across the party system. While the male, unskilled voters with low education opt for the party, support also derives from women, people of all ages, people of all educational backgrounds and those residing in more affluent constituencies.

It is clear that in Greece it is not absolute deprivation, but expectation of deprivation – a deprivation caused by ‘the enemies of Greece’ – which drives Golden Dawn’s support. Despite the second order character of these elections, this may prove a destabilising longer-term trend.

Article by Sofia Vasilopoulou – University of York & Daphne Halikiopoulou – University of Reading.