Fotis Zygoulis is a PhD candidate at the University of Athens. He is also the Head of the Independent Planning and Design Department of the Municipality of Heraklion Attica.

Elina Zagou is based at the County Court in Katerini, Greece.

Since the beginning of the financial crisis, Greece has implemented a number of deep spending cuts, including a reduction in the size of salaries and numbers of staff employed within the Greek public sector. Fotis Zygoulis and Elina Zagou write that although these reforms have had the intended effect of cutting spending, they have not been accompanied by effective policies geared toward improving overall levels of efficiency and the quality of services provided to citizens and businesses. They argue that this is having a negative impact on economic growth and that reforms which rationalise existing administrative structures should be a key priority.

Greece in 2014 is now in the seventh year of a recessionary economic cycle which has generated adverse social, economic and political effects. The Eurozone crisis served as a catalyst for structural reforms, with the country signing agreements on international and European aid that had as a prerequisite a number of radical changes concerning the organisation and functioning of public administration. The financial crisis also exposed the weaknesses within the Greek political system regarding clientelism. The dominance of the patronage system characterised during the previous years both the recruitment of public servants and the public administration’s attitude towards society and the economy.

Greece’s economy in the last 40 years was based on excessive consumption, and external and internal public borrowing. While European funding had been channelled primarily toward consumption, without taking into account the necessary investments, the country’s economic development and infrastructure, or the improvement of good governance, the state was overloaded with an army of public servants. An unequal distribution of the public administration’s structures emerged which resulted in wastage of public expenditure, increasing loans, a huge debt and a public sector which gradually became less efficient overall.

The peculiarity of the Greek public sector is the large size and exorbitant public expenditure on wages, but also the low efficiency along with extremely low quality of services for citizens. However, the efforts of Greece since the end of 1990 to introduce Economic and Monetary Union generated quantitative restrictions on employment policy in public administration.

Recruitment had been diminished, and in many cases the replacement of the outgoing staff was limited to replacing staff on a ‘one to three’ or ‘one to five’ basis (i.e. for every three or five people leaving, one would be hired). Nevertheless, these measures were applied unevenly rather than across the whole public sector and in some cases were gradually abandoned. Since 2009, however, due to the Fiscal Memorandum with the Troika, a strict staff replacement rule in the public sector of ‘one to five’ has been applied. The Medium Term Financial Strategy Government Program extended this rule for the years 2012-2015 and “strengthened” it to ‘one to ten’ in 2011.

In recent years an attempt was made to adapt to the Troika. So there has been the beginning of a series of serious reforms led by the Ministry of Administrative Reform in order to evaluate both the structure and staff of the public service, to remove structures that have nothing to offer society or which coexist with other structures sharing the same powers, and to evaluate the public administration’s personnel. Also in the framework of the Memorandum with the Troika, traditional public structures have been abolished under the ‘mobility’ project in order to fill positions of government, which were in an emergency state.

The economic and administrative restructuring project in Greece involves five key steps. First, it involves the reduction of the operating costs of central government by 200 million euros. Second, it includes the reduction of the public investment programme by 400 million euros. Third, there is the introduction of the ‘one to ten’ rule concerning the recruitment of staff in public enterprises. Fourth, the project includes a reduction of staff salaries in the public sector of 22 per cent. And finally, it involves the overall reduction of 150,000 civil servants.

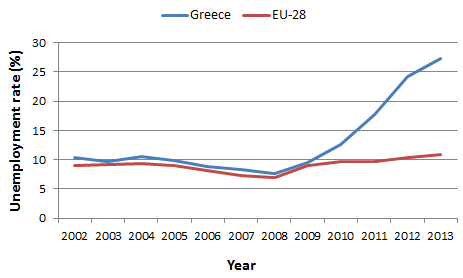

But the crisis has worsened the economic situation of civil servants, with the upcoming reduction of the average wage and the number of salaried personnel by the state budget. The simultaneous reduction in salaries has made the public sector unattractive to the existing personnel. Moreover, the wider impact on human resources has inevitably led to a drop in morale and a reduction of the productivity of employees, alongside an association with increased incidences of corruption. The trend in the overall unemployment rate is shown in the Chart below.

Chart: Unemployment rate in Greece and in the EU (2002–2013)

Note: Figures are from Eurostat

The proposals which have been implemented during the last six years concern management by objectives (suspension and recruitment limitation), meritocracy in selection and promotion procedures, enhancing mobility, a simplified pay system with a single payroll, and the redesign of education systems for public officials.

The Greek financial crisis is a window of opportunity to promote reforms. The decrease of the average wage and the number of salaried individuals through the state budget has been the main priority over the last three years. The cutting of salaries (on average by more than 35 per cent), and the reduction in the number of individuals being paid through the state budget by around 9.9 per cent (76,408 persons) in relation to 2010 has led to a massive exodus of Greek public servants into retirement.

The reduction in the number of civil servants in Greece has not been accompanied by radical changes related to the modernisation of HR management. The lack of goal setting, performance measurement indicators and the continued patronage of the State with regard to the appointment of heads of organisational units in the Greek government means the reforms have not contributed to an improvement in the quality of services offered by Greek civil servants.

The OECD recently produced a report on the consequences of the reduction in salaries of civil servants on the Greek economy. The report clearly shows that the salaries of civil servants by 2010 were disproportionately higher than those of their colleagues in the private sector contributing thereby to a high level of inequality among workers. However the salaries of civil servants were directed mostly toward private consumption. For this reason, the reduction in the salaries of civil servants affected both private sector wages and the general economic cycle.

The crisis has dramatically affected all elements of Greece’s public administration. This includes the decision-making system, and structures for the implementation and monitoring of public policies which, because of their systemic nature, may be considered as “standing weaknesses” of the entire framework for the organisation and the functioning of public administration. Problems such as poor utilisation and misallocation of human resources, the absence of modern methods, techniques and tools administration and a lack of public sector coordination have led to the current undesirable situation within the state.

The problems within the Greek public sector are neither determined nor solely based on its size and cannot be solved simply through a reduction in staff or the salaries of public employees. The most important task today is to upgrade the quality of services provided to citizens and businesses through a rationalisation of administrative structures. The administrative burden of the operation of the Greek public bureaucracy is seriously affecting economic growth – more than the reduction of the salaries of Greek civil servants.

This article was originally published at the London School of Economics’ EUROPP blog.