One cup of coffee per EU citizen. This is a rough estimate of the translation costs of the European Parliament on a yearly basis. A small price to safeguard an important feature of democracy you might argue.

The EU has always been reluctant to reform its policy of linguistic diversity but let’s talk business. Regardless of the costs, is it desirable to have 24 working languages in a democratically elected parliament? No, it most certainly is not.

Language policy within the EU institutions has been a largely ignored subject mostly due to its sensitivity. Languages are closely tied to a country’s cultural identity which automatically transforms it into an emotionally charged topic.

Clearly, choosing a single working language would be easiest and English, with 51 per cent of EU citizens speaking it either as a native or as an additional language, would be the best candidate. However, in a community of 28 countries decisions like this are rarely easy.

The French, for instance, are disgusted by the very idea of English as the sole working language of the EU. Ever since the UK and Ireland joined the European Communities in 1973, there has been a steady decline of le français as the Community’s vernacular. Surely, adopting English as the EU’s official working language would cause Charles de Gaulle to turn in his grave.

Germany, on the other hand, strongly believes Deutsch should remain a working language as it is the language with the most native speakers within the Union. Spain, in turn, might make a case for el español which counts about 500 million speakers worldwide.

276 combinations

But even these countries should have to concede that the present system is prone to error. As the EU expanded over the years, linguistic diversity expanded with it to the point that the EU currently has 24 official languages.

Ideally, speeches by MEPs would be directly translated into the other 23 languages but there is one slight problem: 24 languages gives 276 possible combinations (English-French, Spanish-Polish, etc.) and good luck finding the one person on this planet who speaks both fluent Hungarian and Latvian.

The EP therefore uses so-called ‘relay translation’, meaning, for example, that a speech in Greek will first be interpreted into English after which the English version will be interpreted into Estonian.

Relay translation occasionally leads to a chain of five languages in which case the original speech has been translated four times by four different interpreters. Unlike math where 13 x 17 equals the same everywhere, words are often not unambiguous.

If the first interpreter makes a mistake, then everyone else down the relay will make the same mistake. Accordingly, this impedes a normal plenary session even more than the need for interpretation already does.

Language skills

An important reason to use all 24 official languages in parliamentary debate is the frequently heard argument that politicians are not elected because of their language skills. This may be a valid argument.

Nevertheless, would it be too much to ask of a politician representing his political constituency on the supranational level to be able to express himself in one other language?

Take the current head coach of FC Bayern Munich, Spanish national Josep Guardiola. He learnt German in just a few months because he was motivated to do so. Where there’s a will there’s a way.

However, nothing is likely to change as long as member states will consider the EU as simply an arena for intergovernmental bargaining. If representatives focused on creating policies that best suit Europe as a whole rather than protecting national interests, the language question may become less charged.

Linguistic plurality should and will remain in Europe outside the EU’s governing institutions but a single working language is necessary to avoid confusion and delays during EP debates.

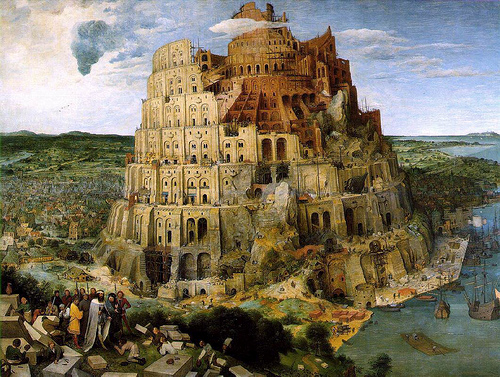

In Genesis 11:5-8 it reads: “Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.” Why not build this Tower of Babel and see if it will stand?

Pieter Cranenbroek, European Affairs journalist based in Brussels, @pcranenbroek