Strengthening the European Parliament has often been viewed as the best method of addressing the EU’s alleged ‘democratic deficit’. Stephen Booth writes that while this perspective has led to the Parliament’s powers being increased successively over recent decades, the effect of these reforms on democratic engagement among EU citizens has been limited. He argues that boosting the role of national parliaments in the EU legislative process would offer a far better route for returning democratic accountability closer to voters.

This week millions of Europeans will cast their vote in the European Parliament elections. The likelihood is that far more will not bother to do so. Many individual MEPs work hard and conscientiously for their constituents. In addition, the reform of the Common Fisheries Policy – and there are other examples too – shows that the parliament can work constructively with national governments. However, despite its ever-increasing powers and the attempts to foster pan-European politics through party groups and foundations, the European Parliament has failed to capture the public imagination.

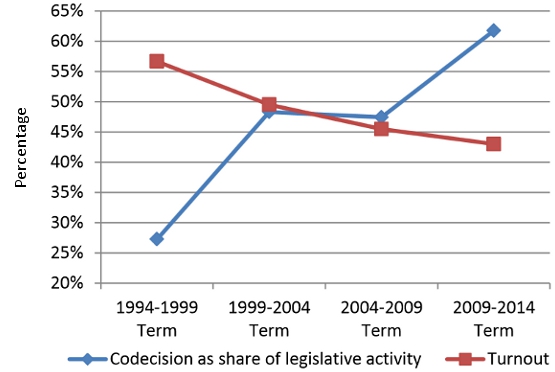

The paradox is now well-known. As Chart 1 shows, despite the use of ‘co-decision’, under which MEPs have equal status with national ministers to pass EU legislation, more than doubling during the last two decades (from 27 per cent to 62 per cent), turnout at European Parliament elections has fallen from 57 per cent to 43 per cent. For those who will vote this week, a large number are likely to vote for anti-EU or anti-establishment parties. According to Open Europe’s estimate, these parties could win around 31 per cent of the vote, up from 25 per cent in 2009.

Chart 1: Voter turnout at European Parliament elections and percentage of EU laws subject to co-decision (ordinary legislative) procedure (1994-2014)

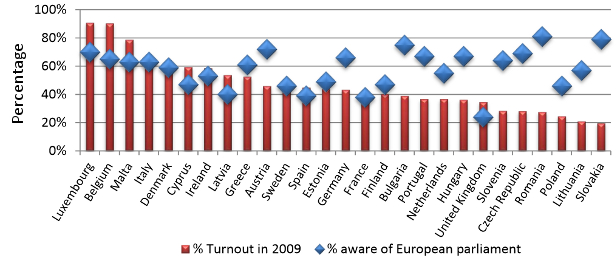

Voters’ indifference or hostility is often assumed to be the result of ignorance. While it is true that many people feel they know little about the EU, data from the European Commission’s Eurobarometer public opinion surveys show that, across the EU, there is no correlation between interest in EU affairs or awareness of the Parliament and voter turnout. For example, in Romania and Slovakia, 81 per cent and 79 per cent of people respectively say they are aware of the European Parliament, but only 28 per cent and 20 per cent turned out to vote in 2009. In the Netherlands, 61 per cent say they are interested in European affairs – the highest in the EU – yet the turnout of voters at 36 per cent is one of the lowest. Chart 2 shows this pattern across EU states for the 2009 European Parliament elections.

Chart 2: Turnout at the 2009 European Parliament elections and percentage of citizens who indicate they have a high level of awareness of the European Parliament

Source: European Parliament Research Service and European Parliament

It is also the case that, in countries where the level of EU integration is politically controversial, voters have been far more motivated to express their view in referenda about how much power the EU should have, than how their MEPs exercise it. For example, in France and the Netherlands, where anti-EU parties are topping opinion polls for the 2014 elections, 69 per cent and 63 per cent respectively voted in the 2005 referenda on the EU Constitution (which became the Lisbon Treaty), while only 43 per cent and 39 per cent voted in the previous year’s European elections. Similarly, large numbers of Danes and Swedes voted to reject joining the single currency in referenda in 2000 and 2003, again outstripping turnout in the countries’ European elections.

At root, the Parliament’s failure to connect with voters across Europe is due to the lack of a European ‘demos’. The EU’s brand of supranational democracy has been artificially constructed from the top down, which is illustrated by the high degree of consensus between the main party groupings. Despite representing national parties of different political traditions, according to VoteWatch, the established centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and centre-left Socialist and Democrat (S&D) party families voted the same way 74 per cent of the time in the 2009-14 parliament, with a heavy bias for ‘more Europe’. This denies voters a genuine choice, thoroughly undermining the very essence of voting.

Rather than learning from the historic failure to connect with voters by increasing MEPs’ power, the parliament looks set to insist on the proposed Spitzenkandidaten or parliamentary families’ candidates for Commission President. This latest top down attempt to connect with voters is likely to go the same way of the others and turn more people off than on. No candidate is ever likely to be able to appeal to enough voters outside of their own country to command a true pan-European mandate. Allowing the EP to hand-pick the Commission President would also disrupt the institutional balance of the EU at the expense of national governments, which continue to enjoy greater legitimacy than MEPs.

As the Table below shows, a recent Open Europe/YouGov opinion poll found that 73 per cent of Britons and 58 per cent of Germans thought that either every country’s national parliament or a group of national parliaments should be able to block proposed new EU laws. Only 8 per cent of Britons and 21 per cent of Germans thought that the European Parliament, rather than national parliaments, should have the right to block new EU laws. The poll also found that, while Britons and Germans thought that the single market is beneficial, a majority of people in both countries wanted decisions over key issues such as EU migrants’ access to benefits, employment laws, regional development subsidies, and police and criminal justice laws to be taken at the national level rather than at the EU level.

Table: Level of government at which British/German citizens believe select policy areas should be determined

Note: See the full Open Europe report for further details

Proposals such as the ‘red card’ would allow national parliaments to combine to permanently block Commission proposals. Instead of repeating the same mistake of addressing the EU’s failure to connect with voters by increasing MEPs’ power, boosting the role of national parliaments in EU decision making would return democratic accountability closer to voters.

This article is based on a longer Open Europe report which is available here