Johan Hellström is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Umeå University. His research interests are in comparative politics, political methodology, political parties and party systems in Europe, political representation and accountability, public opinion, and European politics.

Single party majority governments are relatively rare in Europe, with coalition governments the norm in most countries. However do coalition processes differ between West European states and those in Central and Eastern Europe? Johan Hellström outlines the main factors which influence whether a party enters a governing coalition in Western Europe and contrasts this picture with Central and Eastern European states. He illustrates that while there are important identifiable differences between the two groups of countries, there is some evidence that these differences may be temporary.

The million dollar question before a parliamentary election is generally ‘who wins the election?’ Political pundits make their guesses, betting firms collect their bids and journalist frequently report on the latest polls. In countries like the UK, who will govern is usually clear for everyone as soon as the results of the legislative election are made public. This occurs simply because the majoritarian electoral system tends to produce a single winner with a majority of the seats in parliament, with the general election of February 1974 and 2010 as exceptions (and probably more to come in the future).

In proportional electoral systems a single party may also gain a majority of seats in parliament and thus be able to govern alone, although this is usually not the case. In fact, only about 12 per cent of all governments formed in Europe since 1945 have had a single party majority winner (including the UK, France and other countries with non-proportional electoral systems). Rather, the normal procedure after a legislative election is that representatives from different political parties bargain over who should form the wining coalition – that is, they decide of who gets into government.

What we know about coalition formation in Western Europe

The formation of governments has received its fair share of attention in political science research, especially in a West European context. It is, however, a more recent endeavour when it comes to newer democracies in Central and Eastern Europe. From studies of Western countries we know, unsurprisingly, that winning elections pays. Those parties that gain votes in elections are more likely to enter the cabinet. In particular, being the largest party in parliament is a strong predictor of getting into government, since after an election the leader of that party usually gets the first chance to initiate negotiations to form a new cabinet (i.e. becomes the so called formateur).

In addition, incumbents usually try to stay in government and given that coalition partners still control a majority in parliament, they will try to renew their coalition after an election. However, not all parties get invited to the table in the first place. This is the case for populist or politically ‘extreme’ parties – who more established parties usually prefer not be to be associated with. This is unless, of course, they become too strong to ignore. Ideology also matters in a broader sense for all kinds of political parties. Even though it is sometimes not very easy to see this, parties have some policies they want to implement and are therefore eager to find ideologically close partners to cooperate with. Forming coalitions with parties that have a fairly similar agenda will limit the need for policy compromise on issues that parties agree on.

From this, it follows that the party that has an ideological profile located in the middle in comparison to all other parties, the so called “median party”, has a particularly favourable position (in multiparty systems). Given its position in the middle, it does not matter if a more left-leaning or right-leaning party is trying to form a winning coalition, the median party is likely to be included in both scenarios and is hence likely to become a government member. All these factors are usually good predictors of which parties will form the winning coalition, at least in Western Europe.

Coalition formation in Central and Eastern Europe

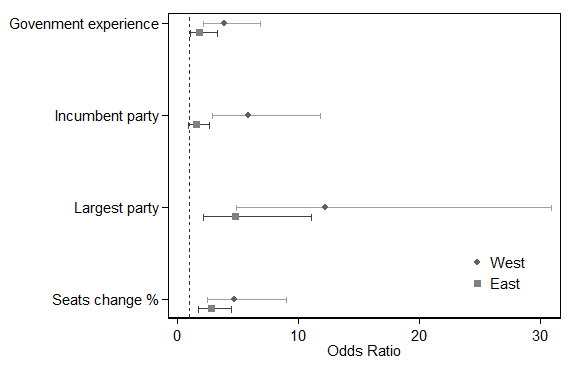

Can we then say that these “empirical truths” also characterise the newer democracies of Central Eastern Europe? Yes and no. In a recent study that compares which kinds of parties get into government in Western Europe, as well as, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), it is shown that although electoral success matters in both regions, there still are some important differences. These differences relate directly or indirectly to the party systems and its constitutive constituent units – the individual political parties. The Figure below illustrates the differences between Western and Eastern Europe.

Figure: Effect of selected factors on the likelihood of a party entering a coalition government following an election in Western and Eastern Europe

Note: The charts show the effect of (selected) predictors on the likelihood of getting into government in Western Europe and Central-Eastern Europe 1990-2009. The effects of the predictors are expressed as odds ratios with 95 per cent confidence intervals. An odds ratio of 1 (shown by the dotted line) indicates no effect; while an odds ratio above 1 indicates that there is an increase in the likelihood of getting into government when the predictor is present or increases by one unit. An odds ratio below 1 indicates that there is a decrease in the likelihood of getting into government. Theoretical range for continuous predictors that are not percentages: Left-right distance 0-200; Electoral volatility 0-100.

First of all, political parties in Central and Eastern Europe are usually seen as weaker or lacking in cohesion and party discipline compared to their Western counterparts, with both members of parliament shifting partisan affiliations and a higher emergence of new parties (genially new as well as party splits and mergers). Secondly, the parties do not compete over left-right policies to the same extent, but instead on their ability to govern (and occasionally even being the least corrupt). From this, it follows that most Central and Eastern European countries have unusually high electoral volatility. That is, voters tend to switch between parties they vote for between elections to a much greater extent than in Western Europe.

Another feature of most post-Communist states is the rift that exists between parties originating in the old communist regime and those that emerged in opposition to the regime. Thus, political parties of the left and centre-left may be limited in their willingness and ability to enter coalitions with Communist successor parties due to their historical legacies and the high electoral costs that may be a result of such allegiances. Even though they may be ideal partners when it comes to the policies they wish to implement, some coalitions may not be feasible due to old divides from the communist past.

All of these differences play a role in which parties get into government in Central and Eastern European countries. Policy similarities in terms of left-right do not seem to play the same role as in Western Europe, and Communist successor parties are usually not invited to join governments. However, there are still some easily observable similarities with Western Europe. Wining pays. Significant seat gains in the most recent election, as well as being the most successful (the largest) party, increases the likelihood of getting into government in both Western and Central and Eastern Europe. Still, with regards to the first two decades of democratic regimes in the region, few of the established findings on government formation in the West can be directly transferred to Central and Eastern Europe.

Nonetheless, things are changing. Since democratisation, political parties have gained more stable positions and Communist successor parties are not the pariah that they used to be. The party systems in some countries (Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia, and the Czech Republic) have consolidated, but are still rather volatile in other countries (Poland, Lithuania and Latvia). At the same time, party systems in West European countries have become more volatile, electoral shifts have become more pronounced, the difference between mainstream parties’ policy positions has become narrower, and the number of feasible coalitions has expanded over time. In the end, the general differences between which kinds of parties get into government between older and newer democracies in Europe may turn out to be temporary.

This article was originally published at the London School of Economics’ EUROPP blog.