Marley Morris is a researcher at Counterpoint on the Recapturing Europe’s Reluctant Radicals project. He has a combined Masters in Maths and Philosophy from the University of Oxford. Prior to his work at Counterpoint Marley was at the Violence and Extremism programme at Demos where he co-authored the report ‘The New Face of Digital Populism’. He has written on populism, social unrest and immigration for a number of blogs, including OpenDemocracy and Liberal Conspiracy.

It has been widely predicted that Eurosceptic and far-right parties will be relatively successful in 2014’s European Parliamentary elections. But how do those that are present currently participate in the Parliament? Drawing on a study of MEPs, Marley Morris finds that while radical-right members are often the least likely to draft reports, they are the most likely to give speeches and ask questions. He writes that despite their strong voice, they often struggle to form alliances within the European Parliament. Any new intake of radical-right politicians in 2014 will be just as conflicted as those currently in the European Parliament.

At a recent event organised by the UK’s European Parliament Information Office, I was struck by Professor Simon Hix’s prediction that the European Parliament elections in 2014 would see two clear dividing lines – one over the pros and cons of the current austerity approach to Europe’s financial crisis, the other pitting federalists head to head with Eurosceptics. In fact, it is likely that Eurosceptics will find notable success at the next elections, whether they come in the form of the anti-austerity Front de Gauche in France or the anti-EU (and most definitely not anti-austerity) UK Independence Party.

One thing is clear: among the Eurosceptics in the next Parliament, a number will come from the populist radical right. While Eurosceptic parties are by no means all radical right, the vast majority of populist radical right parties display some kind of opposition or scepticism to the EU. These parties tend to present a particular concern to mainstream European policymakers because they are seen as hostile to the open, tolerant society that the EU hopes to continue to foster. But, in a bizarre irony, it is these very parties that tend to do particularly well at European Parliament elections. This is because they are seen by voters as ‘second-order’ elections where caution is thrown to the wind: voters take the opportunity to punish their governments and the EU by choosing parties outside of the mainstream.

What does this mean for the populist radical right politicians who are then elected to the European Parliament? In a new Counterpoint study, we analyse data from VoteWatch Europe to explore what these politicians do once in parliament.

The study contains three particularly relevant findings. First, on a set of 10 dossiers from the policy area concerning migrants and ethnic minority rights where there is a high degree of consensus among the mainstream parties, the populist radical right parties are the group that buck the consensus the most. These include the Dutch PVV (who voted against the majority on all ten of the dossiers), France’s Front National, Austria’s FPÖ, Italy’s Lega Nord and the UK’s BNP.

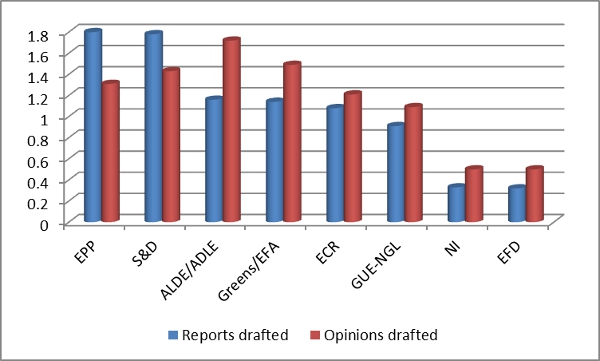

Second, evidence (shown in Figure 1 below) suggests that the populist radical right tends to draft fewer reports than others in the committees of the European Parliament. For this analysis, we have used data about the Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) group and the non-attached MEPs to estimate the behaviour of the populist radical right, as it is these groups that overlap most with populist radical right MEPs. All the populist radical right parties listed above, for instance, are non-attached, with the exception of Lega Nord, which is in the EFD.

Figure 1: Average number of reports per MEP for each of the political groups (July 2009 – July 2012)

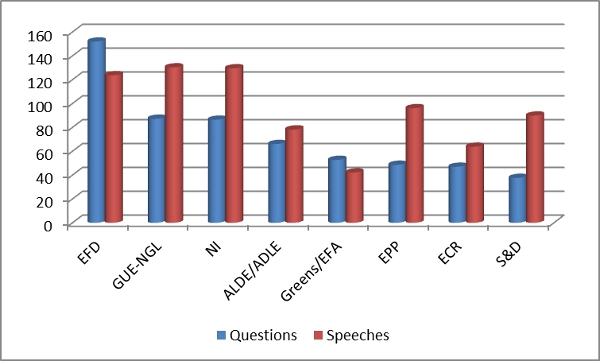

Third, in complete contrast as shown in Figure 2, the EFD and the non-attached MEPs are the most likely groups, alongside the GUE-NGL group, to deliver speeches and ask questions at the parliament’s plenary sessions.

Figure 2 – Average number of questions and speeches per MEP for each of the political groups (July 2009 – July 2012)

The findings suggest that populist radical right MEPs tend not to participate in the committee work of the European Parliament, but they are in general much more active when given the opportunity to speak out at the plenary sessions. This has its logic – these are the European Parliament’s most conflicted politicians, working in an institution that they often oppose. An MEP from the liberal group told me that populist radical right MEPS are in “splendid isolation” in the parliament. It is a struggle for any small political group of MEPs – let alone ones with troublesome reputations – to have influence when the ‘big three’ political groups (the EPP, S&D and ALDE) dominate policymaking. It makes perfect sense, then, that in this context populist radical right MEPs do not put their efforts into policy impact, but instead try to take a stand by speaking out in at plenary. That way they can show to their electorate that they are taking on the EU from the inside.

What does this mean for next year’s elections? Commentators are predicting a boost in representation of the populist radical right. But there are still good reasons to think that these ‘conflicted politicians’ will have disproportionately little impact on policy. First, for the reasons highlighted above, these MEPs tend to focus more on giving speeches and asking questions in the parliament than doing work that has more of a direct policy influence. Second, populist radical right politicians tend to struggle at forging strong pan-European alliances. And they are even less likely to get on with other kinds of Eurosceptics, a number of whom will be keen to avoid any deals for fear of being stigmatised by the press.

This suggests that next year any new populist radical right MEPs are as likely to be as conflicted as the current cohort. How the rest of the MEPs respond will be pivotal – they need to walk a fine line between failing to respond to the concerns of the European electorate and kowtowing to populist demands.

This article was originally published at the London School of Economics’ EUROPP blog.

UKIP aren’t “radical Right”…