Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party retained a comfortable majority in Hungary’s parliament in national elections in April and received more than 50 per cent of the Hungarian vote in the European Parliament elections in May. Johannes Wachs writes that while Fidesz has received criticism from a number of actors within the EU, including the European Commission, the European People’s Party (EPP) has consistently defended Viktor Orbán’s policies. He argues that with Fidesz now opposing the selection of Jean-Claude Juncker as Commission President, it is time for the EPP to take a stronger line against Orbán’s government.

The unique nationalist stance of Hungary’s ruling Fidesz party has been a difficult subject for its parent European People’s Party (EPP). While some EPP members have already made clear they disapprove of the way Fidesz governs, the EPP has continued to support their Hungarian colleagues, as demonstrated through President Joseph Daul’s ringing endorsement at a rally a week before the Hungarian Parliamentary elections in April, and his warm congratulations shortly after their victory. Now, after winning 12 of Hungary’s 21 seats in the European Parliament, Fidesz has come out against the EPP’s preferred candidate for the Commission Presidency, Jean-Claude Junker. In doing so, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has risked alienating those who have supported him in his previous fights with the EU.

The unique nationalist stance of Hungary’s ruling Fidesz party has been a difficult subject for its parent European People’s Party (EPP). While some EPP members have already made clear they disapprove of the way Fidesz governs, the EPP has continued to support their Hungarian colleagues, as demonstrated through President Joseph Daul’s ringing endorsement at a rally a week before the Hungarian Parliamentary elections in April, and his warm congratulations shortly after their victory. Now, after winning 12 of Hungary’s 21 seats in the European Parliament, Fidesz has come out against the EPP’s preferred candidate for the Commission Presidency, Jean-Claude Junker. In doing so, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has risked alienating those who have supported him in his previous fights with the EU.

Four years of antagonising the EU, four more to come?

Fidesz’s previous four years in government saw numerous conflicts between Hungary and international organisations like the EU and the IMF. Examples include the Venice Commission’s critique of amendments to the constitution, Green MEP Rui Tavares’ report on the situation of fundamental rights, and the European Commissioner for Justice, and EPP member, Viviane Reding’s activities to censure the government for new laws concerning, among other issues, the media and the judiciary.

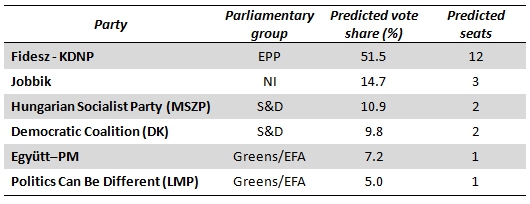

Fidesz and nominally independent pro-Fidesz civil organisations like the Civil Union Forum (CÖF) havereacted to these criticisms by designating them attacks on Hungarian sovereignty and on the Hungarian people. This discourse nourishes the growth of the national-conservative and far-right rhetoric embraced by Jobbik, the far-right party which came second in the European Parliament elections with 14.7 per cent of the vote, as shown in the Table below.

Table: Result of the 2014 European Parliament election in Hungary

Note: Fidesz and the Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP) form an alliance. For the other parties see: Jobbik;Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP); Democratic Coalition (DK); Together 2014 (Együtt); Dialogue for Hungary (PM); Politics can be Different (LMP). For an explanation of the parliamentary groups, see here.

Recent history does not look better. Fidesz and Jobbik’s increasingly close relationships with Russia sit awkwardly next to the EU’s attempt to resolve the Ukrainian crisis. The controversy over the nearly completed monument commemorating the German occupation of Hungary and the election, with Fidesz votes, of former skinhead and current Jobbik MP Tamás Sneider as a deputy speaker of parliament, are dangerous signs.

Fidesz and the EPP

Over two years ago, the German news magazine Der Spiegel ran a piece questioning the European People’s Party’s unwillingness to criticise Hungary’s political situation. Officially, the EPP opposed the Tavares report, but mathematically, assuming that Eurosceptic MEPs did not endorse the report, some EPP MEPs must have abstained or voted for it. A more important institutional example is Commissioner Reding’s procedures against Hungary. Not only is she a member of the EPP, she was appointed and supported by Jean-Claude Junker while he was the Prime Minister of Luxembourg. The conservative Hungarian press cites this fact and Junker’s federalist view as the reason for Prime Minister Orbán’s refusal to support his candidacy for the presidency.

Individual figures in the EPP have been critical of Fidesz. Recently, German Chancellor Angela Merkelcriticised Prime Minister Orbán, albeit in rather vague terms. This challenge is especially muted compared with Orbán’s previous rhetoric on Germany’s involvement in Hungarian affairs. Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk was much harsher in response to his Hungarian counterpart’s call for autonomy for the Hungarians living in Ukraine. Yet these exceptions only underline the general policy of tolerance for Fidesz within the EPP. Indeed, Orbán has enjoyed the confidence of the EPP for over a decade. Heserved as an elected vice president of the EPP following his electoral defeat in 2002 and was re-elected to this post in 2006 and 2009.

Other political parties in the European parliament have increasingly pressed the EPP on their tacit acceptance of Fidesz. During the debates between the lead candidates for Commission President, Guy Verhofstadt of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe attacked Juncker for the EPP’s support of Orbán, describing him as a politician who “is changing the constitution every five minutes when he needs to be re-elected.”

The head of Germany’s SPD, Sigmar Gabriel, also suggested after the elections that Fidesz and Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia do not belong in the EPP. Gabriel is of course highly interested in weakening the position of the EPP and their lead candidate as the negotiations for the Commission Presidency begin. If Fidesz and Forza Italia are removed from the EPP caucus, Gabriel’s Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) would be the largest group in the European Parliament.

Orbán’s Hungary represents a novel challenge for the EU from an institutional perspective. There is no clear mechanism to censure a member state short of the application by the European Council of Article 7 of the Treaty of the European Union, which, subject to unanimous agreement to discuss and qualified majority to confirm, suspends a Member State’s voting rights. The EPP’s defence of Fidesz during the proceedings around the Tavares Report blocked any attempt to create new mechanisms.

A dangerous form of nationalism

Hungary’s current political situation cannot be simply compared with previous problem governments, such as the Wolfgang Schüssel’s coalition with Jörg Haider’s Freedom Party in Austria, or Vladimír Mečiar’s Slovakian governments. Besides the strong legislative majority and centralised power it has, and beyond the support the party receives from the EPP, Fidesz’s fight with the EU has taken on an ethnic-nationalist tone that makes it especially dangerous.

The anti-EU sentiment in Budapest does not focus on bureaucrats, regulations or economic burdens, but rather interference in the areas of constitutionality, democracy and the rule of law. As Csaba Tóth arguesin a recent Financial Times article, in this sense Orbán does not fit the mould of other Eurosceptic party leaders like Marine Le Pen or Nigel Farage.

Slavoj Žižek recently cited Hungary as an example of the retreat of fundamental rights to freedom, equality, education and healthcare. He quotes Prime Minister Orbán in 2012: “Let us hope, that God will help us and we will not have to invent a new type of political system instead of democracy that would need to be introduced for the sake of economic survival.” This kind of ideology is a new problem for the European Union, closer to the ethnic nationalism Ian Buruma attributes to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Unfortunately it seems this outdated mentality already has an important foothold in the EU and the EPP’s continued tolerance grants it undue legitimacy.

Thanks to London School of Economic and Johannes Wachs

About the author

Johannes Wachs

Johannes Wachs

Johannes Wachs is based in Budapest with research interests in the Hungarian and European political landscapes. He is an MSc graduate of Central European University.